Jibran’s Perspective

State machines - Why and how to use them in web development.

Dec 18, 2022What is a state machine?

I think Wikipedia does a very good job of defining a state machine.

A finite-state machine (FSM) or finite-state automaton (FSA, plural: automata), finite automaton, or simply a state machine, is a mathematical model of computation. It is an abstract machine that can be in exactly one of a finite number of states at any given time. The FSM can change from one state to another in response to some inputs; the change from one state to another is called a transition. An FSM is defined by a list of its states, its initial state, and the inputs that trigger each transition.

In software development, a state machine is usually represented by some aggregate data structure; an object in an OOP language, or a hash-map in a functional language like Clojure. A state machine can also be saved to your DB as a row in a table.

This object has fields for current state and the data in needs to do it’s job. There is also code associated with this object that defines how it transitions between it’s states.

An example

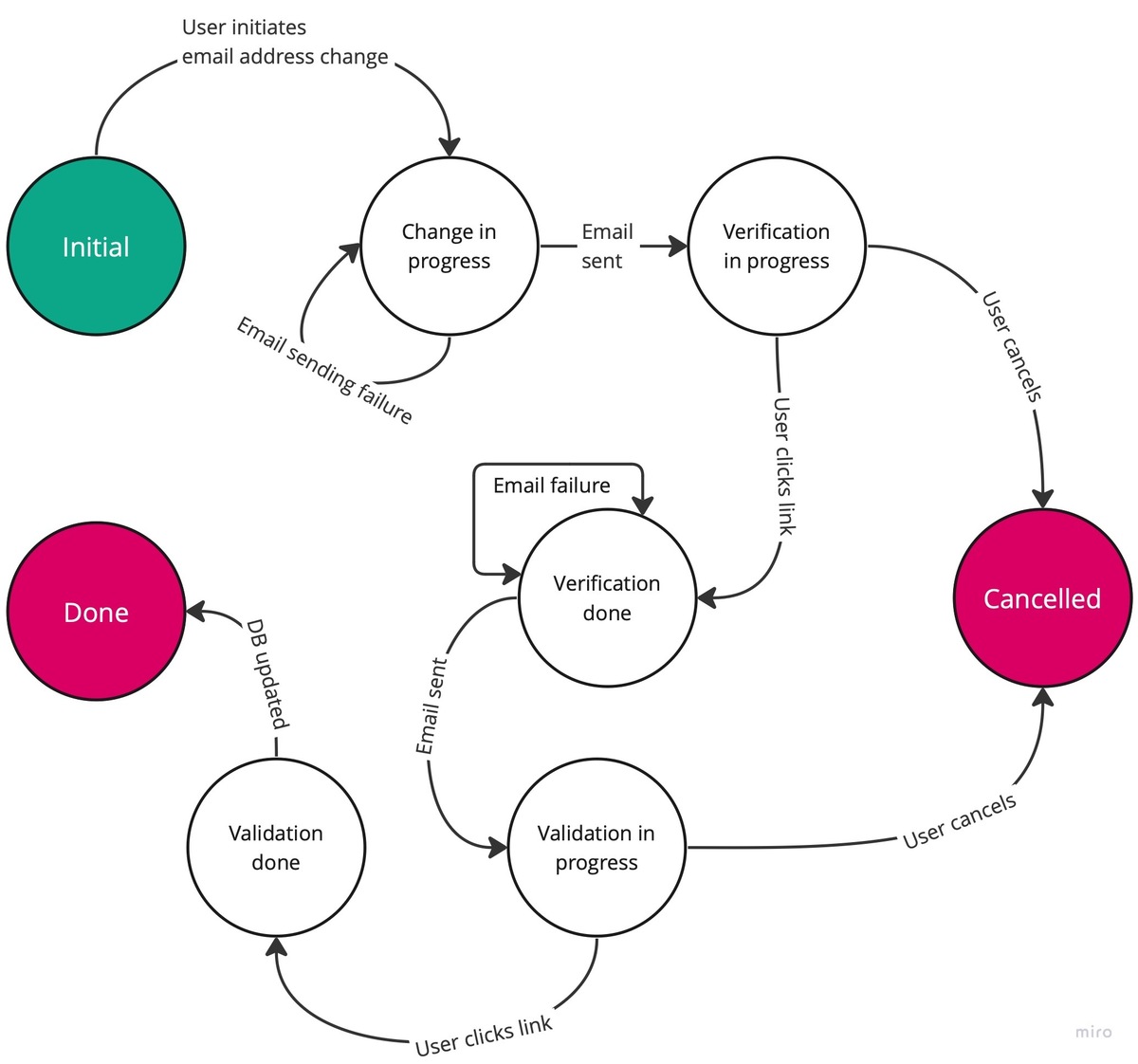

Let’s look at an example. A user trying to change their primary email address, which is also their username.

The states are:

- initial => This is the starting state in which the machine is initialized.

- change-in-progress => The user has asked for the email address to be changed. verification-in-progress => We have sent an email to the old email address, asking the user to confirm the change.

- verification-done => The user has verified the change. validation-in-progress => We have sent an email to the new email address, asking the user to validate that they can receive emails there.

- validation-done => The user has validated their new email address.

- changed => The change has been applied.

- request-cancelled => The request has been cancelled.

Transitions are:

- initial => change-in-progress. Initiated when the user requests the change via a web form. change-in-progress => verification-in-progress. We have sent the verification email to the current email address.

- verification-in-progress => verification-done. The user has verified that they intended to make this change by clicking a link sent to their existing email.

- verification-done => validation-in-progress. We have send the validation email to the new email address. validation-in-progress => validation-done. The user has validated the new email address by clicking a link in the email sent to it.

- validation-done => changed. We have made the change in our DBs, and run any other processing required for this change.

- any => request-cancelled. The request was cancelled by either the user or our systems.

You could also add states for verification or validation failures. Also for failures of our system to send an email.

The reason to have states like change-in-progress and validation-done is to make sure we only change to the in-progress states after we have sent the email. A failure in our email sending system should not put the user in a state where they need an email to proceed further but our system thinks the email has been sent. There are more states that can be added to make this more robust. I’ve skipped any states that deal with error conditions (validation failure, etc). For this hypothetical system, we can transition to request-cancelled but you might want more granular states to record exact points of failure.

How do we communicate/document state machines?

While we can describe state machines with written descriptions, it’s much easier to use state diagrams. These are the standard way of describing a state machine, and are great at communicating how a state machine functions.

What’s the point?

Looking at the example above, you may be thinking; what’s the point of using a state machine? It seems like we’re needlessly adding a layer of complexity to a simple feature that most web applications built today support happily without a state machine.

Here’s a secret. All software development is building state machines.

Computers are themselves FSMs. As is all the software we write on top of them. It’s just that we don’t normally think of the enormous space of possible states, instead we think in terms of values of variables and what they represent in our software.

Thinking explicitly in terms of FSMs for small parts of our software makes it easy to reason about it, which is why it’s very useful to model our software as an FSM on smaller scales, in critical modules where we must be absolutely sure of how the software will react to different inputs.

A practical example

I think this whole state machine business is a lot easier to explain with a code sample. Xstate is a popular JS library that makes it easy to build state machines. Instead of copying the code here, I’ll just link it.

Here’s a tutorial from the Xstate site that walks you through building an app that displays post from a sub-Reddit. Notice how the code is simpler to reason about. You’re almost breaking the functionality into it’s constituent pieces; what to do while the posts are loading, what behavior to expose when the posts are loaded, and how to react if loading fails.